How to Fix Grandma’s Network on Verizon FiOS

tech · · 6 min readIn my family, the person with the fastest Internet connection is… Grandma, a Vietnam War refugee who has never used a computer in her life. This is by virtue of her residence on a main road in the great state of Delaware, which gets fiber TV and Internet service through Verizon FiOS. She subscribes to the cheapest Internet plan so that the grandkids can tap away at their tablets during family gatherings. And on FiOS, the “lowest tier” is a blazing-fast symmetric connection: 100 Mbps down, 100 Mbps up.

It really isn’t fair, is it?

Grandma’s 20th-century tract home, like Grandma herself, was thrust only reluctantly into the digital age. It has no data cabling whatsoever besides two landlines and two coax ports, which, naturally, are both located on the extreme corners of the house—the worst possible positions to place a Wi-Fi access point. So for many years, the family ISP shitbox sat on one end of the house or the other, saddling the opposite side with all of the classic symptoms of crappy Wi-Fi coverage: buffering videos, sluggish webpages, frequent disassociations, and frustrated kids. This fall, I discovered one of my uncles (bless his heart) had attempted to cover the dead spot with a cheap access point and powerline networking kit from TP-Link. Immediately, my heart sank—powerline networking is almost always bad news. I marshaled together two laptops and ran iperf to test the performance of the link. It was a bottleneck… to put it mildly. On a network with a 100 Mbps uplink, the powerline connection achieved a whopping 12 Mbps.

Right then and there, I decided it was time to blow up Grandma’s home network and start over. It had to go, all of it—the extra AP; the powerline adapters; even the Verizon router itself, a venerable Actiontec MI-424WR that hasn’t received a security patch in over a decade. My plan was to junk everything and install a whole-home Wi-Fi mesh system using Ethernet-over-coax (MoCA) technology for reliable backhaul. (A cross between “option 9” and “option 10,” for those of you who made their way here from DSL Reports’ FiOS guide.) We’re talking 802.11ac, dual-band, wired backbone, baby. At first, I set my sights on Google Wifi, but I found the price tag of Linksys Velop—the economy dual-band model can be had in 2-packs for just $100-150 total—a little more palatable. I wasn’t worried about cheaping out because, thanks to the MoCA backbone, I wouldn’t be relying on the performance (or lack thereof) of Velop’s wireless repeating.

I consider Belkin a third-rate brand, but I have to hand it to them for the job they’ve done on their Velop product. For example, if you run a home network with multiple access points, it’s important that they support roaming assistance—the 802.11k, v, and r standards—without which Wi-Fi clients tend to “stick” to the first AP they see and refuse to switch to another station, even if the-signal-quality-is-garbage-and-another-AP-is-_right-there_-so-why-the-hell-wouldn’t-you-switch-god-damnit. In the consumer space, basically nothing supports roaming assistance except for whole-home mesh systems—including, of course, Linksys Velop. Velop also autodetects the presence of an Ethernet connection between its nodes, and makes use of it for backhaul. (Some contemporary mesh systems, unbelievably, lack Ethernet ports altogether!) And bonus points for Velop’s online management interface; it’s refreshing to be able to manage a network without installing yet another smartphone app.

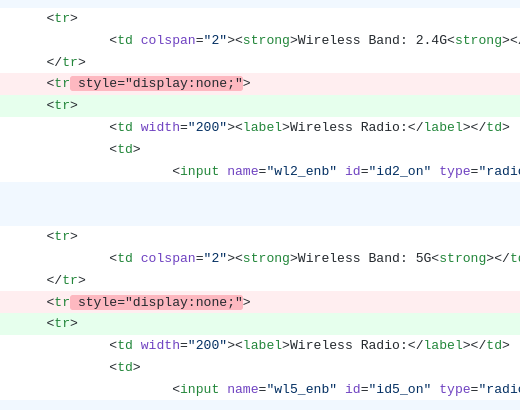

For my MoCA adapters, I cheaped out and bought a pair of Actiontec WCB3000N‘s, which regularly go for $20 each, used. Testing with iperf clocked their maximum speed at about 100 Mbps. (The newest stuff on the market can exceed gigabit speeds, but I couldn’t justify paying triple the cost for speeds nobody in Grandma’s house would ever need or use.) Each WCB3000N comes with a pair of very outdated 802.11n Wi-Fi radios, the idea being that the device can act as a coax-backed “Wi-Fi extender.” Um, thanks, but no thanks; I’d just like the MoCA part, please. But what’s this? No web interface option to disable Wi-Fi? WTF?! Hilariously, there is indeed a control—it’s just hidden by a little bit of CSS.

You see, WCB3000N’s are so cheap because the market is flooded with examples that were handed out by ISP’s. Mine came from Spectrum, who apparently removed the ability to disable Wi-Fi to make their product “idiot-proof.” One brave soul on GitHub got the GPL source to compile and released a custom build that restores the missing control. Unfortunately, there’s one bug still unresolved: The setting to disable the 2.4GHz radio doesn’t stick after a reboot. Pooey. I turned off SSID broadcast on that network and called it a day.

There are some special considerations to mind when working on a FiOS network. First, the cable boxes require an IP connection to download TV guide data from Verizon. Although some models (including the one my Grandma has) have Ethernet ports, they are not activated, and the connection has to be made using their builtin MoCA adapters. Fortunately, the boxes can link with any commodity MoCA adapter—including the WCB3000N I was using to network the Velops. Second, the remote DVR and on-screen caller ID features won’t work if a Verizon router isn’t the gateway. In my case, the loss of neither of these mattered to Grandma…

Another complication is the connection from the router (my base Velop node) to the Optical Network Terminal on the side of the house, which can be made via either MoCA or Ethernet. Contemporary installs use Ethernet, but older FiOS installs—including, you guessed it, Grandma’s—used coax, probably so the installers could spare themselves the trouble of running a new Ethernet line. The coax connector on a FiOS-branded router conceals two MoCA adapters: the “LAN-side” one, which runs on channel D1 and connects to the cable boxes, and the “WAN-side” one, which runs on the less-common channel C4 and connects to the ONT. The use of differing frequencies keeps both MoCA network segments logically separate.

| Network Segment | MoCA Frequency | Connected Devices |

|---|---|---|

| WAN | C4 | Router; ONT |

| LAN | D1 | Router; cable boxes; Wi-Fi; Ethernet |

Running a new Ethernet line wasn’t an option—Grandma would’ve strangled me if I broke out the drill and started punching holes in her precious house. So, I needed a MoCA adapter that could operate on channel C4 and talk to the ONT. Turns out these adapters have gone nearly extinct! The Arris MEB1100, which Verizon distributes to FiOS customers, seems to be the only one still in production. But I wondered if it was possible to dodge this purchase by placing Grandma’s existing FiOS router into bridge mode. The Actiontec web interface has no obvious option to do this; but as it turns out, it is indeed possible!

The key is the “Network Connections” screen, which allows you to modify the router’s internal network topology to your heart’s content. You can accomplish a bridging configuration by detaching the “Ethernet/Coax” interface from the “Network” bridge and bridging it with the “Broadband Connection” interface. Unfortunately, if your model lacks the ability to separate the Ethernet and coax interfaces, you’ll have to disable the LAN-side MoCA adapter.

By doing this, you’ll lose all access to the web interface except through the Wi-Fi hotspot, which will become its own, isolated network segment. Just set the SSID to something unique, like MI424WR_Admin, and use the same WPA password printed on the unit so that it’s easy to remember in the event you need to access the configuration screen again. (It’s not a security concern to keep an Actiontec router in service like this, because the web interface is not accessible from the Internet—or even your own LAN.) Then, when you plug the WAN port of your own router into one of the LAN ports on the Actiontec, your router will receive a public IP address, and you’ll be off to the races.

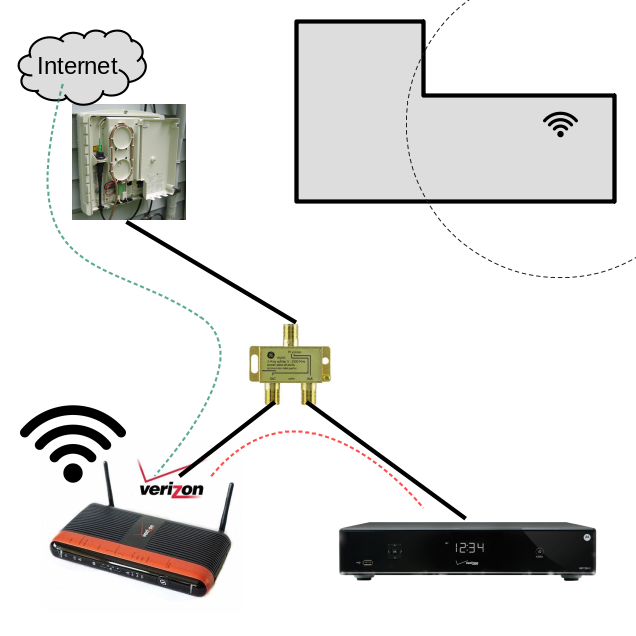

So, several equipment overhauls and a few coax splitters later, Grandma’s network went from this:

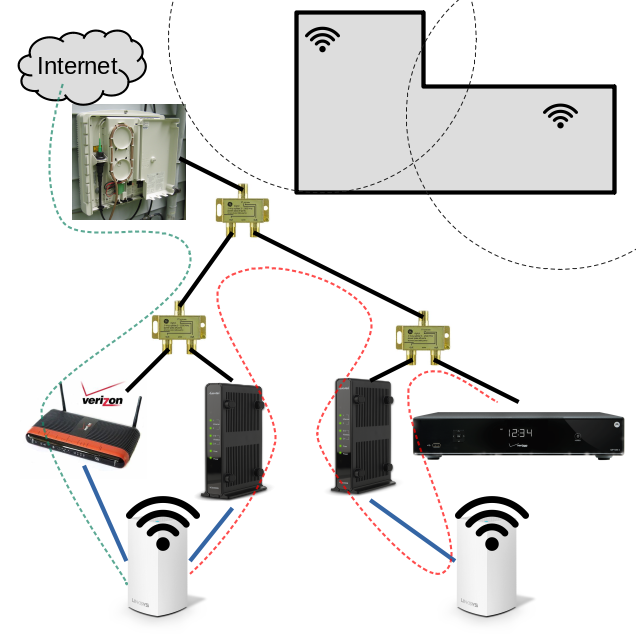

To this:

Did I over-engineer the crap out of it? Probably. But at least you can start a download anywhere in Grandma’s house and get the full 100 Mbps.