Gone: Clearing the Path for California’s Last Freeway

writing · · 6 min readWestpark is a neighborhood like any other in Central Bakersfield. It’s filled with single-story ranch homes from the 50’s and 60’s; its streets are wide, clean, and lined with orderly parked cars; its lawns are neatly divided by fully matured palm trees.

But Westpark is a neighborhood under siege.

Over the past several years, city bulldozers sliced a wide, sterile arc directly through the heart of the neighborhood; they razed at least 300 homes and 120 businesses. And now, where the humble homesteads of hundreds of families and retirees once stood, there is nothing–just woodchips and orphaned cross-streets as far as the eye can see.

The city was clearing the way for a titanic construction project. It’s building a six-lane freeway, called the Centennial Corridor, that will someday wind its way through Westpark in a trench. But until the excavators get the go-ahead to carve out the highway’s sunken alignment, the land will sit barren, in a bizarre state of limbo.

On one foggy January morning, I took a childhood friend of mine to Westpark to document the neighborhood as it stands in 2018. Our plan was to meet up with a mutual friend of ours and take photos while getting some exercise. I told them we were exploring an “abandoned neighborhood,” but none of us was really prepared for the scene we came upon.

In Our Path

“Oh, s—t.” His jaw dropped.

I was with driving with my friend to Westpark’s Centennial Park. We were traveling along California Avenue at the point where the new freeway will cross over; and here, we got our first glimpse of the scale of the demolition.

It was a paralyzing sight: An open gash that appeared out of nowhere and receded into the limits of the fog. An entire neighborhood, thoroughly eviscerated, robbed of its houses and neighbors.

We met up with our other friend and hit the streets.

We walked freely through the demolished lots, which resembled earthen moonscapes.

Looking to the north, the existing Westside Parkway in the distance.

Not all of it’s gone. The roads, sidewalks, streetlights, and electrical boxes are still here–eerie remnants of the homes they once served. Eventually, they’ll be gone too, replaced by overpasses crossing a below-ground Centennial Corridor.

The construction zone is a surreal scene. There are signs of activity–parked equipment, piles of dirt–but none of it is fenced off. It’s a bombed-out war zone you’re free to enter at your own peril.

My friend looked out onto California Avenue, its automobile commuters going about their daily business. “All of these people just driving by,” he said, “and nobody really gives a s—t.”

The Road to Serfdom

For many Bakersfield residents, the Centennial Corridor has been a long time coming; a missing link in the city’s nonsensically disconnected freeway network. On one end of the project lies State Route 58, an important regional highway that connects Bakersfield to all points further east. Highway 58, finished in 1976, was always intended to continue past its western terminus at State Route 99.

But in the 70’s, facing the full heat of the environmental movement, California put a stop to all new freeway construction. So the city and the state gave up on extending Route 58–but the idea came roaring back to life in the new millennium. In 2005, local congressman Bill Thomas secured a windfall of federal dollars for Bakersfield road projects: the so-called “Thomas Roads Improvement Program,” a $630 million rider attached to the SAFETEA-Lu transportation bill.

Bakersfield jumped at the opportunity to realize the long-lost west-side freeway. Much of it could be aligned on relatively barren land along the banks of the Kern River, and the city quickly constructed those segments using TRIP funds. All sections of the so-called Westside Parkway were open by 2015. But connecting the new Parkway to Route 58 would be a far more difficult endeavor.

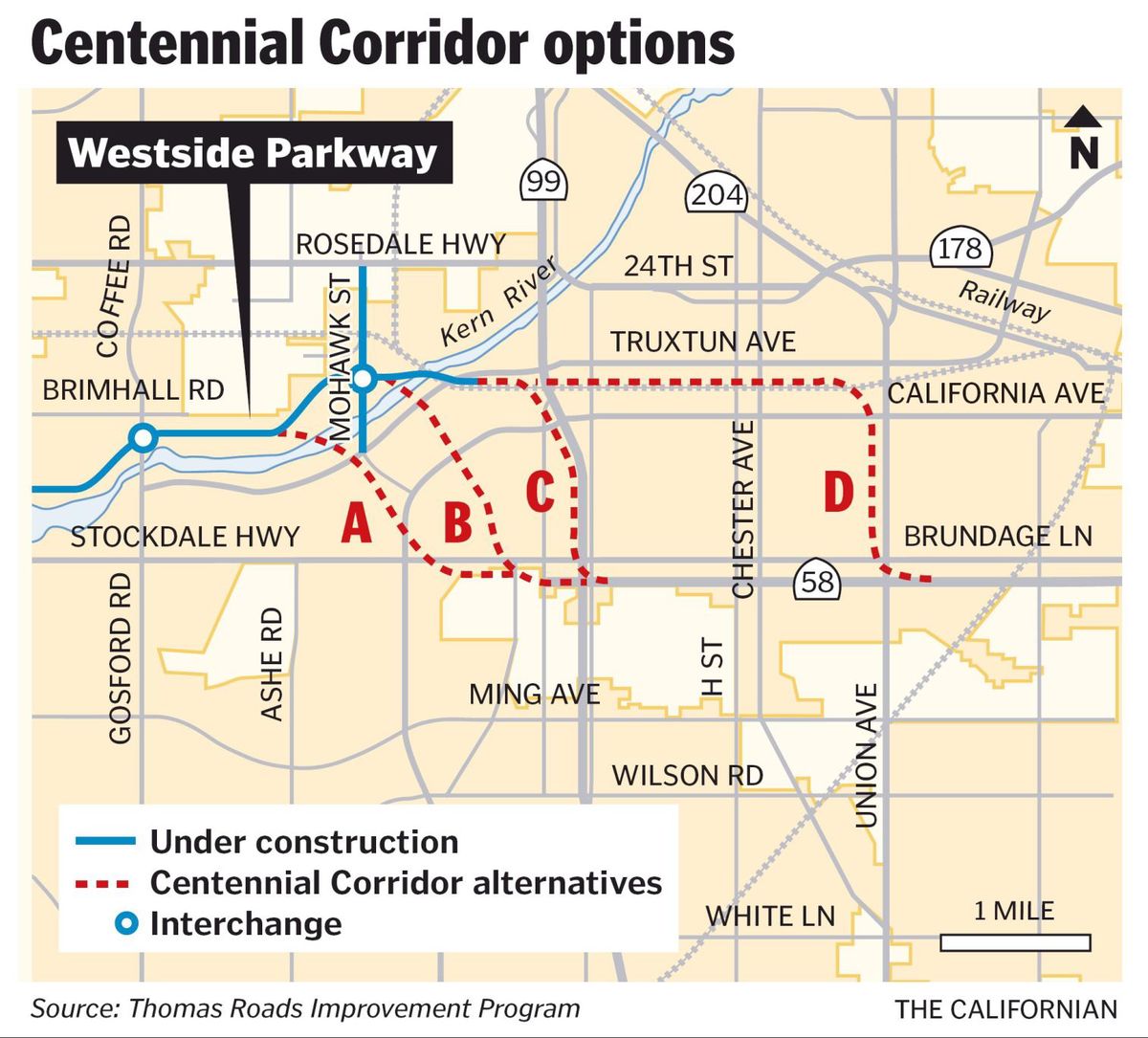

A, B, C, or D. Caltrans, the California Department of Transportation, told Bakersfield to fill in the bubble. Which alignment should the proposed new freeway take?

The alignments Caltrans studied for the Centennial Corridor, courtesy of the Bakersfield Californian.

A targeted offices and businesses. B targeted Westpark homes. C paralleled existing freeways. D, the most ludicrous option, upgraded surface streets on the east side. There was also a no-build option, which you might call option E. But as we all know, “none of the above” is never the answer.

In 2001, the city assured Westpark it would never approve alignment B. But seven years later, city council sent it to Caltrans for study anyway. Fast-forward to 2012: Caltrans determined that alternatives A, C, and D all would have impacted parks and historic properties. That would drive up costs and endanger federal funding.

The correct answer was alternative B.

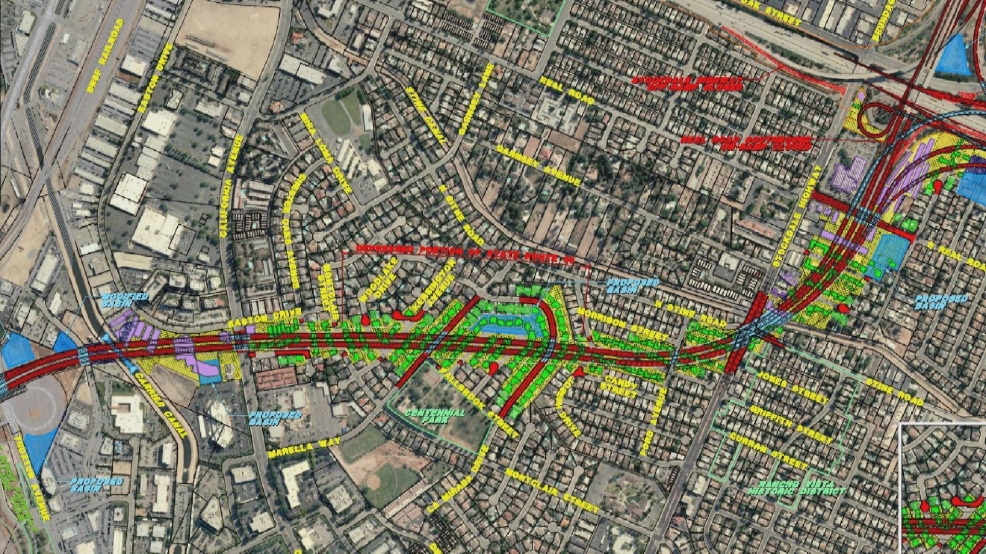

The footprint of the Centennial Corridor and the Westpark properties slated for demolition.

Westpark residents pleaded with Caltrans and city council: Don’t destroy our homes. Don’t build this freeway.

The city began to acquire the properties in the path of the Centennial Corridor. In spring 2016, it awarded the first contracts for demolition. Not everything came down at once–at first, some businesses and residents stayed. Like the streetlights, they stood as monuments to the people, households, and relationships that were slowly dissolving away.

One-by-one, the city demolished them too.

On the Beach

For now, life in Westpark is largely business as usual. Children and teens shoot basketballs at Centennial Park; an elderly couple greets us on our walk; houses and cars are clean and well-kept; the empty lots are remarkably free of litter.

But this won’t last. We know what happens when neighborhoods get bisected by freeways. The highway will split the neighborhood in two, physically and socially; the promised sound barriers won’t work; the property values will plummet.

Who is to blame for the situation in Westpark?

Everyone interested in city planning knows the story of Robert Moses: He was a bureaucrat who governed the construction of public works in New York City for several decades. Moses cleared out and destroyed countless neighborhoods to build his pet parkways and highways, which in turn created endless amounts of traffic congestion and urban sprawl. In the process, he diverted funding from New York’s public transit and commuter trains, killing their expansion plans and allowing them to fall apart.

You may not live in New York City, but Moses’ urban development schemes became the template for the twentieth-century American metropolis. Cities all over the United States rushed to duplicate Moses’ ribbons of concrete, and quite a few hired him to draw up the plans.

Moses is reviled today because he was anti-democratic. He was never elected to his post, and his activities were shrouded in the executive privilege of public authorities. In his time, Moses was hailed as the “Master Builder,” but in retrospect, writers now call him “the sadist who wrecked New York.”

But for the Centennial Corridor, there is no boogeyman or Robert Moses to point to; just the voters of Bakersfield and Kern County.

If you speak to any Bakersfield citizen that doesn’t live in Westpark, they’d probably agree that the Centennial Corridor is necessary. They’d agree with the regional planners, and congressman Bill Thomas, that the freeway is necessary for reasons of “regional connectivity” and “congestion relief” and “future development.” Then, of course, they’d point to the hard proof on the map: a tantalizing missing link between two major freeways that Bakersfield can’t afford not to build.

As Robert Caro wrote in The Power Broker, the definitive biography of Moses’ life, Moses took the view that the ends justified the means.

Moses himself, who feels his works will make him immortal, believes he will be justified by history, that his works will endure and be blessed by generations not yet born.

Evidently, Bill Thomas shares that point of view.

Ten years from now, everyone is going to see the significance and the importance of what we’re doing. There have to be decisions made, and we’re making decisions. We’re making decisions in the most reasonable environment.

So if Bakersfield is going to be build this freeway after all, then I hope we at least remember that we threw a community under that bulldozer. I hope we can say that, in the end, we did give a s—t.

The Thomas Roads Improvement Program calls this project the Centennial Corridor, but I call it “The Last Freeway”; the last highway California will ever run through an established urban neighborhood.

Bakersfield wanted a new freeway. We paid the price. Westpark is on life support, and the city is set to spend $270 million it does not have. Next time–when planners draw up new freeways to serve the traffic that will inevitably come–will we pay that price again?

Looking into the distance from Centennial Park.